Incorporating Career Relevance in the Classroom

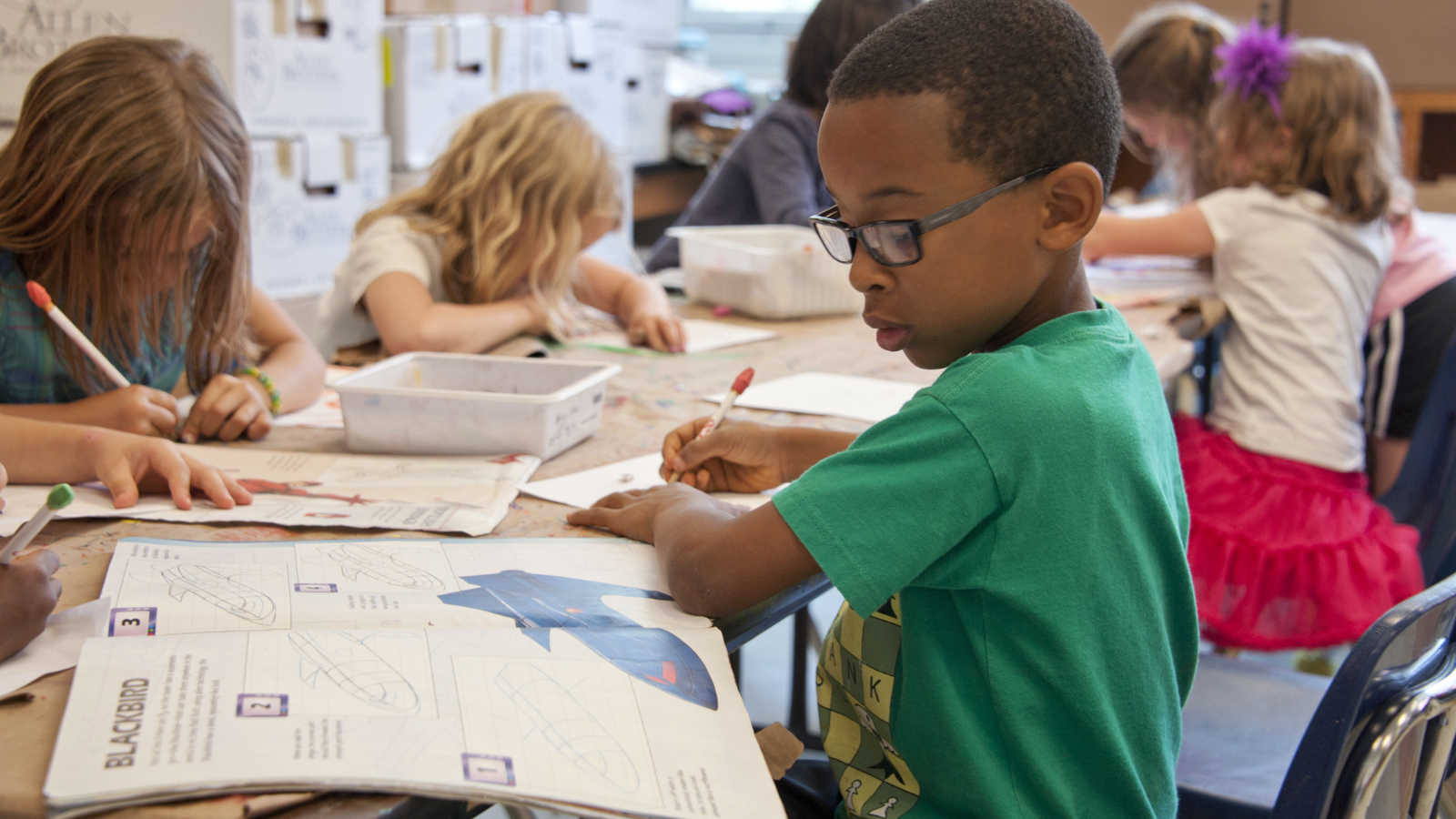

For almost a decade I’ve started the school year by asking my urban elementary students to draw a picture of what they think a scientist does at work all day. When I walk around the room, I often see pictures of white-haired men dressed in lab coats working at a lab bench mixing chemicals. Over the course of the year, I teach lessons that expose my students to a variety of different experiences that mirror what real scientists do. We engineer vehicles that are powered by rubber band energy to learn about motion and explore ecosystems by collecting data about organisms in our schoolyard. During these experiences, I make connections for students to the work of different scientists by telling them we were acting like a biologist while writing questions about animals in our science notebooks or acting like a geologist while we were observing rocks. At the end of the year, I would ask my students to draw a scientist again and I saw vastly different pictures. They were drawing themselves doing the experiments we did in class throughout the year. It was evident that their perceptions of science and scientists were changing. This made me wonder if their aspirations about how science could be part of their future were also changing.

Incorporating Career-Connected Learning

We live in a time where the landscape of science education is ever-evolving with the addition of technology and innovation. We are more than a decade into the implementation of the Next Generation Science Standards and STEM learning has infiltrated school districts across the country. This creates a rapidly changing work environment for teachers who are tasked with educating students that will pursue careers that don’t yet exist. Twenty years ago we didn’t know app developers or YouTubers would be career options. After reflecting on the context we are living in and thinking about how I could prepare my students for their future endeavors, I saw all of this change as a chance to incorporate more career-connected learning into my elementary science classroom. This was a way to support my students in building their identities as scientists and engineers.

I did this by incorporating more career-connected learning into the units I was teaching by providing students with the opportunity to hear stories about people's journeys to finding their careers and what it was like to work in the field. I searched for short videos on YouTube and utilized a variety of texts. Many of the videos I found involved scientists and engineers that discussed what they did at work and how they worked with others. For example, when we were learning about expanding our subway system our curriculum included information about Geotech engineers. We read about their work and watched videos about how important it was to work on a team for long-term projects like expanding subway tracks. Hearing about how people were connected to their current careers and the work they do each day was a way for me to show my students a diverse array of people in those careers including women and people of color.

After students heard these stories of real people, I implemented project-based learning tasks by Defined Learning throughout the year where they could take on the role of someone in a particular career and apply what they learned about different science concepts. In early elementary, we did an engaging performance task called "Cupcake Baker" which gave students the opportunity to play the role of cupcake bakers, applying the concepts we learned about solids and liquids to the baking process. We frequently referred to ourselves as cupcake engineers as we utilized different engineering skills in the process of designing new cupcake flavors for our own bakeries. In upper elementary, we took on the role of climate resiliency scientists studying our local watersheds and learning about permeable and non-permeable surfaces in our city. In both of these examples, students learned about how people in these careers were managing budgets, plans, and feedback from others to inform their work.

.

Impacts of Career-Connected Learning

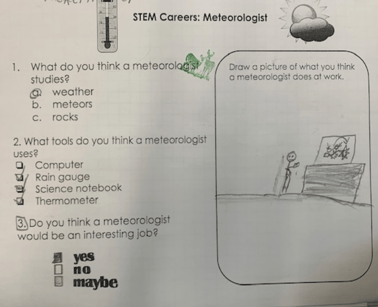

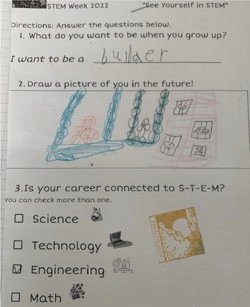

Over time, I saw the impacts of career-connected learning on my students’ attitudes toward science learning, cooperative learning, and life goals. I noticed how much more excited they were about what they were learning and how it could benefit them in the future. Seeing people that looked like them working in a career they didn’t know existed helped them to create new aspirations for themselves. Career-connected learning also opened the door for conversations about other skills we used in science class like being part of a team, problem-solving skills, and time management. In addition to exposing students to a wide variety of careers, we took time to discuss their career aspirations and think about how they are connected to STEM disciplines. This created space for discussions about how a wide range of careers from chefs to meteorologists use science, technology, engineering, and math as part of their jobs. This also helped me to build relationships with my students and incorporate connections to careers that interested them. Going beyond these generalized careers and embedding career-connected learning into my yearly scope and sequence has exposed my students to experiences that helped them build knowledge and new aspirations for their futures. Career-connected learning throughout K-12 education is essential to prepare students to solve complex multidisciplinary problems and feel empowered to become change-makers in our society.

About the Author:

Holly Rosa is currently a science specialist in Boston Public Schools where she has worked for 15 years. Holly has served students in various roles including as a STEM specialist, science teacher leader, teacher-researcher, and district-level Science Director. She believes we can all learn to think, act, and communicate like scientists and engineers by taking an apprenticeship approach to learning. She has a passion for teaching science writing to multilingual learners using Systemic Functional Linguistics and enjoys creating professional learning experiences for educators that focus on creating a classroom culture where students and teachers are collaborators in co-constructing knowledge.

Learn More About Career Connected Learning @ Defined

Discover how Defined Learning helps students build future-ready skills through project-based learning, STEM, and career exploration.